During the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, Anglo-Irish explorer Ernest Shackleton (1874-1922) led three expeditions to the polar region. His adventurous life was set down in print, and he joined the ranks of Antarctic explorers Captain Robert Falcon Scott (1868-1912) and Admiral Richard E. Byrd (1888-1957), whose names call to mind a bygone time of intrepid adventure.

The mind of a young boy in Chicago was inspired by their travels and buzzing with dreams of exploring the world.

That was Sam Adams (1927-2022), and at the age of 7, he spent most of the summer of 1934 at the Chicago’s World’s Fair, reveling in an exhibit that included the boat that Byrd used on his Antarctic travels. Decades later, Adams would make two trips to the polar region: at ages 86 and 88.

Sam Adams, Dancing inmates, Western New Mexico Correctional Facility, Grants, New Mexico (ca. 1990s), “Detention” series, Sam Adams Collection, Palace of the Governors Photo Archives

“He got injured on that trip,” says Kathleen McIntosh, Adams’ wife (his second) of 35 years. “They ran into some foul weather, and he got tossed around quite a bit. But he never gave up.”

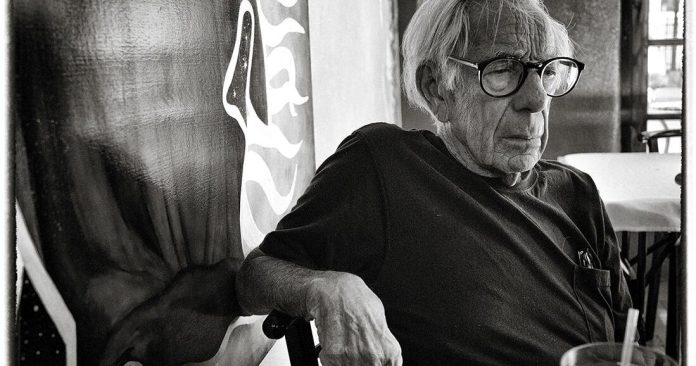

A noted literary agent for film and television, Adams moved to Santa Fe in 1989 and spent the last few decades of his life quietly pursuing his lifelong passion for photography. Adams, 94, died in January.

“Two weeks before he died, if you had said, ‘How about we take a trip to the Northwest Passage or go around Cape Horn?’ he would say, ‘Let’s do it,’” says Adam’s longtime friend, Pulitzer Prize-nominated author, and producer Howard Korder. “He was always fascinated by ships. He bought himself a beautiful boat that I believe had been shipped over from Japan, and he regularly sailed that on the weekends. I think, for him, the greatest pleasure in the world was to be in a comfortable berth on a ship with some character, heading to someplace that he’d never been before.”

A memorial for Adams is planned for Saturday, April 16, at El Museo Cultural de Santa Fe, where several of his photographs will be on display.

Rodeo riders stretch in preparation for competition at the Rodeo de Santa Fe (ca. 2008), “No Pastime for Old Men” rodeo series, Sam Adams Collection, Palace of the Governors Photo Archives

Once upon a time in Hollywood

In some ways, Adams was born of the old guard, in a time when Hollywood was in the midst of its golden age. Raised by a single mother, he often found himself left to his own devices.

“When we first arrived in California, Mom and I lived in a small apartment around the corner from Warner Brothers’ Beverly Theater,” Adams told author Laurie Gwen Shapiro in oral history recorded during his final Antarctic trip in 2015. “I was still my own babysitter, and occasionally I’d snag a good seat in the public bleachers to watch the [red carpet] premieres Someone like Bette Davis would pop out of a limousine, then Humphrey Bogart.”

After serving 18 months of active duty during World War II, Adams returned to a job as a messenger at Warner Bros., which hired him while he was in high school.

Tango dancers embrace in the streets of the San Telmo district, Buenos Aires (ca. 2012), Sam Adams Collection, Palace of the Governors Photo Archives

“Every day I delivered messages to Bogart, Errol Flynn, Alexis Smith, and Bette Davis,” he told Shapiro. “I saw Bette Davis throw a fit, as well as Edgar G. Robinson. Bogart asked me to take friends of his on a studio tour. Whatever he asked me, I said, ‘Yes, Mr Bogart!’ He liked my attitude.”

Clowning around on the set of Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Bogart pulled a prank on actor Alfonso Bedoya, Adams said. The Mexican actor was riding a mechanical horse and firing his gun for a scene in the film.

“Before shooting the scene, Bogart came up behind me and whispered, ‘When [director] John Huston calls ‘cut and print,’ just walk off the sound stage.’ I said ‘Yes, Mr Bogart!’ He whispered that to everyone on set. So, Huston calls ‘cut and print!’, and everyone leaves, except Bedoya riding that mechanical horse. Someone even closed the lights, and Bedoya was on a horse at 90 miles per hour and left alone in the dark screaming for help.”

Adams went on to work for the Los Angeles Examiner, the Armed Forces Radio Services, and the Beverly Hills Press before joining the Hollywood Reporter in 1955. Impressed by Adams’ theater and opera reviews, actor and producer Sam Jaffe hired him as a junior agent at the Jaffe Agency.

“He just decided one time, on his own, to go to the South,” photographer Don Usner says. “He went to small towns, churches, barbershops, grocery stores, and took pictures.” Baptist Church service, Covington, Tennessee (ca. 2002), “American South” series, Sam Adams Collection, Palace of the Governors Photo Archives

That was the beginning. Under the auspices of Adams, Ray & Rosenberg, Adams would negotiate deals for Caddyshack, Klute, and Saturday Night Fever, as well as book-to-film sales for Margaret Atwood and Isaac Bashevis Singer.

“He always said that being a literary agent was sort of a misnomer,” McIntosh says. “He represented screenwriters, directors, and producers in movies and television. He represented screen rights for published works.”

Eventually, the couple moved to Santa Fe, attracted to the weather, the light, the mix of cultures, and the eclecticism.

Photo opportunity

Maybe you don’t know Adams’ photo work, but you’ve likely seen it in The New Mexican, at the New Mexico History Museum’s exhibition Photography of Sam Adams (2015), or in numerous exhibits at El Museo. His black-and-white street photography is bold, often dramatic, sometimes humorous, and always humane.

Adams’ analogue photography is in the collection of the Palace of the Governor’s Photo Archives as part of the Legacy Project, an initiative to document the last 50 years of New Mexico’s visual history. Adams’ contributions are included along with work by Cary Herz, Herbert A. Lotz, Tony O’Brien, Jack Parsons, and Donald Woodman, husband of artist Judy Chicago.

pull rate

“He was almost always right in everything he said about photographs and their compositions: how to analyze them, how to crop an image.” — Photographer Don Usner

In 2005, Adams was awarded the New Mexico Council on Photography’s Eliot Porter Award.

“In many ways, he was like some very cranky but extremely interesting uncle that I never knew I had,” says Korder, who considered Adams his mentor in photography. “There’s an old joke about two Jews, three opinions. That was the case for Sam and me. We argued about everything, including the things that we agreed on. He was almost always right, which was endlessly infuriating.”

Three boys at play on a street, Mallorca, Spain (2014), Sam Adams Collection, Palace of the Governors

Photo Archives

Korder, a writer by profession and a photographer by avocation, met Adams at the wedding of the daughter of a mutual friend more than 25 years ago.

“Sam was, by nature, a very inquisitive person, and he asked me what I was interested in,” Korder says. “I mentioned photography, and we were off to the races.”

What impressed Korder the most about Adams as a street photographer was his fearlessness and his indefatigable nature. He’d call Korder a skulker, because the younger photographer’s habit was to find a corner and photograph his subjects surreptitiously. Not so with Adams, who didn’t blanch at what some might consider an invasive approach.

“That’s the job of a street photographer,” Korder says. “He was good at winning people over. He would go, ‘This is what I’m looking for, and I’m going to go get it.’ And he would.”

Professional photographer Don Usner also considered Adams a mentor.

“I spent a lot of time with Sam in the darkroom,” says Usner. “It was the most creative and interesting darkroom for sure. He had big stereo speakers and hundreds and hundreds of classical albums, especially opera. We’d put that on and print and talk and look at pictures.”

pull rate

“He loved [composer Johann Sebastian] Bach, who was so mathematically, symmetrically contrived, in a way, and yet conveyed such intense emotion. I see that in his pictures. They’re beautifully rendered artistically but convey such feeling.” — Photographer Don Usner

Usner and Adams worked together this way until the oughts, when darkroom photography became something of an anachronism, and both photographers switched to digital.

The switch from film to digital wasn’t easy for Adams, whom Usner describes as “an analog person crammed into a digital world.”

“He was very impatient,” Usner says. “He was used to being hands on. You did it physically. He would point out the illogic of software like Lightroom and Photoshop, how it was completely backwards and didn’t make any sense. And he was completely right. I had to tell him, ‘Look, Sam, it’s like gravity. You can’t fight it.’

“We went back to see his darkroom a couple of years ago,” Usner says. “A lot of my equipment is still in there, but it’s all cobwebs and dust. It’s poignant to see what’s happened to such a vibrant, creative space. There’s an analogy there with what’s happened with film in general.”

Final frame

Adams’ health began to decline about five years ago, McIntosh says, and it grew worse in the wake of the coronavirus.

“You know, the pandemic hit elderly people really hard,” she says. “The isolation, the lack of opportunity for exercise, and lack of social contact was very difficult for him. He was a very social person.

“The day he died, Don Usner brought pictures over to show him. I have a photograph of Sam lying in bed, hooked up to oxygen and everything, completely enlarged in these pictures. He never lost his passion for that.”