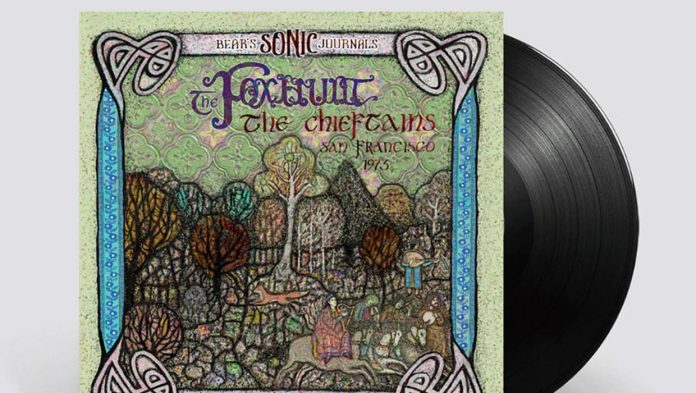

The Foxhunt, The Chieftains Live in San Francisco, 1973 & 1976 is a previously unreleased 2CD gem from the Bear’s Sonic Journals series, and is a joint release by The Owsley Stanley Foundation and Claddagh Records.

t was produced by Owsley ‘Bear’ Stanley, the Grateful Dead’s legendary sound engineer who recorded the Chieftains’ performances.

The Irish trad group appeared on those shows in San Francisco at the invitation of the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, one of their biggest fans.

Hawk Semins of the Owsley Stanley Foundation (dedicated to the preservation of Owsley’s 1,300 live concerts) knows all about it.

“San Francisco in the 1970s was a fertile place in American musical history – not only in the evolution of the San Francisco sound, but also as a musical crossroads where people were coming from all over the world to play.

“I think Jerry Garcia listening to The Chieftains is a great example of that. He heard his musical ancestors, his musical grandfathers,” says Semins.

“Jerry was fascinated with bluegrass — and he could hear, particularly in the fiddle playing, the connect between The Chieftains’ music, Irish traditional music and the bluegrass which he loved.

Close

Hank Semins of the Owsley Stanley Foundation

Hank Semins of the Owsley Stanley Foundation

“Jerry was a walking encyclopaedia of Americana and roots music, and he was absolutely aware of where it came from.

“He heard The Chieftains through Chesley Millikan, the Irish national who relocated to the US, via Sam Cutler, the Rolling Stones’ manager who then became the Grateful Dead’s manager. He brought Chesney over.”

“He said to Jerry: ‘Hey, you’ve got to check out these guys, The Chieftains. They’re in town.‘ He was introduced to their music and then said: ‘Let’s get them on the radio, KSAN.’

“Jerry sent a stretch limo to The Chieftains’ hotel to pick them up and take them to the radio show. That was a kindness that Paddy never forgot.

Video of the Day

“Remember, this was 1973, their first US tour, and they were relatively unknown in the United States. They’d a great reputation in Ireland and a growing reputation in the UK,but they are still part-time musicians – and for a rock star like Jerry Garcia to send them a limo was an amazing gesture, worthy of Elvis Presley buying brand new Cadillacs for people.”

“The Chieftains did the radio show and played live, and Jerry invited them to open for his blue grass band the next night. That’s the first recording that’s presented on the new release. It was Jerry staging this perfect pairing of bluegrass music and its Irish traditional progenitor.”

“What I think is so fascinating about this story is that it took 19 more years before The Chieftains sat in with bluegrass artists and did a record with them – starting with Another Country and Down the Old Plank Road. The seed for that idea – Paddy told me this – came from his experience in San Francisco on that first tour.”

[Released in 1992, Another Country is a collaboration with Ricky Skaggs, Don Williams, Colin James, Emmylou Harris, Willie Nelson and Chet Atkins, which won the 1993 Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Folk Album. Down the Old Plank Road: The Nashville Sessions was released in 2002, and is a collaboration with Ricky Skaggs, Vince Gill, Lyle Lovett, Martina McBride and Alison Krauss.]

Did Paddy keep up the relationship with Jerry Garcia?

“Yes, he did. I don’t want to convey the impression that they were best friends or anything, but there was a great mutual respect – and over the course of two more decades they did communicate.

“Paddy was invited backstage at one of the Grateful Dead’s Madison Square Garden’s concerts in New York in the early 1990s. I think Jerry wanted him to play with the band, but Paddy demurred. At that time, Paddy discussed doing an album with Jerry but it never panned out.”

What do you think Paddy recording with the Grateful Dead would have sounded like, if they ever had gotten round to make that album?

“I think it would have been an absolute delight – like Celtic-infused jazz!

“In the early 1990s, in an East Coast show I attended, I distinctly recall hearing the Dead play a Celtic jam during a segue from the Drums/Space section of their show… after talking with Paddy, I bet it was the same tour when they invited him backstage at Madison Square Garden and Jerry wanted him to sit in. They had Irish music on the brain then, I think.

Close

Jerry Garcia, centre, with Grateful Dead manager Rock Scully and author Tom Wolfe on Haight/Ashbury. Picture by Ted Streshinsky/Getty

Jerry Garcia, centre, with Grateful Dead manager Rock Scully and author Tom Wolfe on Haight/Ashbury. Picture by Ted Streshinsky/Getty

“A few years later, after Jerry had passed, Paddy was speaking on the radio about the KSAN show he did with Jerry back in 1973 – and he said how he’d love to get a copy of the tape. Jerry’s widow Deborah Koons Garcia brought Paddy a tape of the Chieftains’ concert.”

I was in Paddy’s house earlier and there were boxes and boxes of tapes of Chieftains’ recordings. Could there be long-lost recordings among them?

“Paddy mentioned a number of recordings. They may be in Wicklow, in Paddy’s place in Annamoe. There are a few things in particular that Paddy mentioned that, frankly, I said: ‘We’d love to help you with that!’

“So, I was led to believe that there were tapes [with unreleased music] on them, but it may be a challenge to find them. The tape that Deborah Koons Garcia gave Paddy was down in Annamoe, along with the photograph of The Chieftains getting into the limo.”

What are your memories of Paddy doing the interview for the CD?

“I spent 12 hours with him for the interview. The CD has about five minutes of snippets from the interview, things that accentuate points that we raised in the liner notes. He was dead six weeks later. We were absolutely devastated. He was so enthusiastic about the project.

“He was thrilled to reconnect with the music. He had so many ideas and was so helpful in identifying things.

Close

Paddy Moloney backstage at Glastonbury 1983. Picture by David Corio/Redferns

Paddy Moloney backstage at Glastonbury 1983. Picture by David Corio/Redferns

“One of the things that blew us away was that Paddy brought his tin whistle everywhere with him, and when he would explain musical concepts, he couldn’t help himself from illustrating it on the tin whistle.

“He would talk, then he would play and sing. You could see he was still composing, even in every conversation.

“We would talk about Ali Akbar Khan and he would say: ‘Ah, I saw Ali Akbar Khan play and I wanted to play with him, I had this great idea of how the tin whistle would work with a sarod [Ali Akbar Khan’s instrument] and it went something like this.’

“He also adored Doc Watson. He started playing ‘Arkansas Traveller’ from memory. ‘Oh, I love Doc Watson! He plays at a million miles an hour!’ Then he dives into ’Arkansas Traveller’.

“We had given Paddy copies of our Doc Watson and Ali Akbar Khan releases, and he knew both musicians. With respect to Ali Akbar Khan, Paddy heard him play and then he composed a piece that he thought would be perfect for a collaboration someday.

“The collaboration never occurred, but Paddy still remembered the melody and played it for us on his tin whistle.”

Close

Paddy (seated) with Brian Masterson (second left), assorted Chieftains, Kris Kristofferson, Willie Nelson and others at Windmill Lane Studios

Paddy (seated) with Brian Masterson (second left), assorted Chieftains, Kris Kristofferson, Willie Nelson and others at Windmill Lane Studios

Paddy was a musical genius. Of this there is no doubt. The Chieftains’ long-term sound engineer Brian Masterson of course agrees. He recorded an interview with Paddy five weeks before he died, and it’s included on the album.

“The recordings of The Chieftains live in San Francisco on these CDs are sonically unique, because of the way Owsley recorded the music,” says Masterson, who is also the recording boffin behind the setting up of Windmill Lane studios.

“It was quite amazing the sound that he got. He put up all these omni-directional mics, one for each person, and then miked the front of the stage. So what you’re hearing is a combination of the hall sound, and then the close sound of the musicians playing.

“It is extraordinary, because for someone who was not part of the tradition of Irish music, he really figured out how it would work – those balances.

“That was the first thing that was remarkable about it. Then this was the first concert that the Chieftains had done in the States.

Close

Owsley Stanley, sound engineer and Sixties LSD king

Owsley Stanley, sound engineer and Sixties LSD king

“There was so much fun on stage because of how Owsley miked it. You could hear little bits of repertoire and slagging which makes it quite fantastic.”

“Of course ‘The Fox Hunt’ is incredible, and the set that became the ‘Drowsy Maggie’ set was great, too. They played this one chorus over and over and in-between choruses each individual musician goes and does a little show off of their solo instrument. It is a lovely concept.

“Of course, Derek Bell – who was always the joker in The Chieftains – would go off into something completely different. And then the two whistles, Paddy and Seán Potts. That’s the other thing about Paddy. He was a very good whistle player. And he always had the whistle with him.

“They were playing in San Francisco, remember. Can you imagine going over to San Francisco, coming from early 1970s Dublin and other parts of Ireland, suddenly landing in San Francisco where no one knew who they were? That soon changed.”

How did you come to be involved in this project?

“I have a studio at home in Sandycove. I got a call from Hawk in July of last year. He explained the project to me and said they wanted to come over and interview Paddy. They wanted to do in my place because he said Paddy would prefer to come to my home.”

“We blocked out two days and it was two seriously wonderful two days of the loveliest nostalgia and fun and laughs.

“Paddy sat on the sofa in Sandycove. He talked about everything – his childhood, going to school, learning music at very early age – and with fair modesty really, talking about being good at it. He took to it and found an ease with music. He talked about the early days and Seán Ó Riada a little bit. And then he talks about his philosophy of how it all should be.

Close

The Chieftains with Ry Cooder. Picture by Judith Burrows

The Chieftains with Ry Cooder. Picture by Judith Burrows

What was his philosophy as you saw it?

“In later years, he did musical crossovers a lot, but he would maintain that he was always very true to the tradition and that he always honoured the tradition. But he wasn’t afraid to move away.

“There’s this Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann thing – who do fantastic work – but they’re very purist in their outlook for Irish music, and Paddy always felt that this was a little bit constraining.

“He thought it was okay to have accompaniment, and it was okay to have harmonies, and it was okay to have someone else play from outside that field, and in latter years it was okay to have superstars.”

It was almost like the Latin Mass – and Paddy wanted to broaden it out for the people?

“Exactly, there was a strictness to it. Paddy didn’t have that.

“I’ll tell you a great story that I think illustrates Paddy’s talent, his genius, and his unbelievable ability to just react and gather people in and make it work.

“It was when The Chieftains were invited to China in 1983 by the Chinese government. They were coming out of the Cultural Revolution and were trying to open up things a little bit. But only a little bit! They wouldn’t invite rock bands or anything, but they invited The Chieftains, sort of as cultural ambassadors from Ireland.

Close

Some Chieftains and some Rolling Stones

Some Chieftains and some Rolling Stones

“I was luckily, happily, part of that. There was no internet, no mobile phones, but there were suspicious clicks on the line when you picked up the phone in your hotel room.”

“There was very little communication possible. This idea that The Chieftains were going to play with this Chinese traditional orchestra – a Chinese harp and a Chinese fiddle and flute – was incredibly complex, because there was no way that there could be any significant communication about it. We got off the plane in Beijing with a huge mixing desk and all our instruments.

“Two days later we had recovered from the jet lag all met in a lobby in the hotel. We were like: ‘Where do we do from here?’ We had an interpreter, but that was it.

“But Paddy realised the Chinese musicians knew tonic sol-fa [the system of naming the notes of the scale: do, re, mi]. Paddy had grown up with that and learned that in school, and he could sing any in tonic sol-fa without even thinking about it.

“So suddenly Paddy is singing out these notes. And suddenly the Chinese musicians, through the interpreters, were jumping up and down and saying, ‘We know what you’re singing!’

“They were writing it down in their notation. We had minders all the time. We were extremely well-treated but the film crew weren’t treated well. It was a great trip. Rita and all the wives were there.

Close

Garech de Brun and Paddy Moloney

Garech de Brun and Paddy Moloney

“Garech de Brun [the founder of Claddagh Records] was there too. He was a hoot. God knows what they made of him.

“He was correcting the Chinese cultural people on the bus. They would point out that such and such a thing was from this or that dynasty, and Garech would pipe up: ‘Not true! Not true! It’s actually from such and such a dynasty!’“

Was he right or wrong?

“My guess is Garech was probably right. But the gigs were incredible. It was a huge auditorium, and they didn’t know what to do or how to react, but musically, it was wonderful.

“The Chieftains did their own stuff and then on came the Chinese and they played together. Paddy got them to play their traditional music and he welded the Chieftains on to that. There were a few tunes where it went the other way.

“Paddy really did it on the fly. It was really by the seat of his pants. He was writing it only when he arrived. But he pulled it off.” [You can hear the results on The Chieftains in China album, recorded by Masterson, and released in 1985.]

How would you describe Paddy Moloney?

“Ach, where do I start to sum up Paddy Moloney? He was like a perpetual motion machine. His energy, his drive, and his opportunism – in the nicest possible way, in terms of creativity and commercial situations – that was just hugely part of what he was. He was always looking for a little angle.

“Look at all these people who would have been foreign to the strictly traditional scene – starting with Van and moving on to the likes of Sting, The Rolling Stones, Roger Daltrey and all the others – that was Paddy seeing angles, seeing opportunities, seeing a way to spread it and enlarge it, make it something bigger than just purely musicians just sitting onstage playing music.

Close

Derek Bell, Martin Fay, Sting, Paddy Moloney and Matt Molloy

Derek Bell, Martin Fay, Sting, Paddy Moloney and Matt Molloy

“To work with other artists from different musical fields now is almost standard – but back then, when Paddy started doing it, it certainly was not.

“He probably would have got a certain number of frowns I’d say, maybe even from other members of the band.”

Can you remember the first time you met him?

“It was shortly after Windmill Lane opened in 1978. Guinness wanted to do a advert. They wanted something to make it stand out and I got the Chieftains in to record it. I was the house engineer, if you like.

“I was a bit nervous – because I’d heard these stories about Paddy. That he had a very puritanical approach to how the Chieftains should sound.”

In what way?

“I heard rumours that he wanted it much more like you would record a chamber orchestra. He wanted it real – not falsified, not enhanced.

“Anyway, The Chieftains came in and we got on great. Paddy was delighted. And that was it. He was happy because I obviously delivered sonically what he wanted, and he was able to relate to me. We just hit it off in terms of music and as people. We clicked.

“He was very, very driven. It was all work, work, work with him.”

Close

Van Morrison (centre) and The Chieftains

Van Morrison (centre) and The Chieftains

That was the Seventies?

“Yes. The first album I worked with The Chieftains was Boil the Breakfast Early in 1979, their ninth album and it was already starting to push the boundaries. There was a little more fire coming into it.

“Matt Molloy joining put a lot of energy into that side of things. He and Seán Keane became such admirers of each other. They were both virtuoso musicians, fiddle and flute. They found each other within the band. It was that virtuosity that both of them had.

“Martin Fay was the guy who played all the lyrical slow airs and things like that. For the reels and jigs it was Matt and Seán backed by Derek Bell.

“They would have a Donegal style, or a Clare style, and they would meet somewhere in the middle. You would see the looks going back and forward between them. And Paddy, of course, was well able to keep up with all of that.

“He was running everything, doing all the arrangements – by which I mean how the tunes went together, which tune followed which, how you’d get from one tune to another.

“He would probably compose them on the last flight or something because they were always on the back of bits of envelopes and things. It would A, A, B, C, C, pause, bodhran roll into the second tune, A, A, B, C, C. He could always hear it in his head.”

That’s genius, isn’t it?

“It is. He knew how he wanted the tunes to go together. He knew the pace of it, and the build, the ups and the downs, and the dynamics of the piece. Everybody would sit around in the studio. Then Paddy would come in and it would be right down to business.

“Paddy would reel off the arrangements of the particular set of tunes that they were going to do. He would talk it through. ‘We’ll play that part twice – that’s A, A, B, B. And then Derek, will you lead us into the next one and slow it down there…’

“This could take ten minutes by the time Paddy got to the end – and then Martin, who was maybe doing the crossword in the newspaper while Paddy was saying all this, would look up and say: ‘What did you say there, Paddy?’”

What did you work on after the Boil The Breakfast Early?

“Everyone! I think I worked on 26 or 27 Chieftain albums and film scores. Don’t ask me to name them all. Paddy liked what I did.

“He knew the sound he wanted because it was in his head. The thing about Paddy was you’d be working on these €350,000 mixing desks and using the highest quality multi-track recordings – and he would want to listen to the final mix on a tiny machine with a little speaker. That was how he judged it. That was his way of doing it during the mixing.

Close

A young Sinead O’Connor sings with The Chieftains

A young Sinead O’Connor sings with The Chieftains

“I worked on the collaboration albums like Long Black Veil too. The quality of the people on them was amazing,” he says, referring to the likes of Sinead O’Connor, Marianne Faithfull, Mark Knopfler, the Rolling Stones, Ry Cooder, Sting and Van Morrison.

“Some of it was recorded in Ireland, some of it in England, and some of it in LA. I went over and worked with the Stones. They were happy to be directed by Paddy. That was the whole point of it. I sang with Mick Jagger on the chorus of the ‘Rocky Road To Dublin’. They wanted another Irish voice. Myself and Kevin [Conneff] and Mick sang.

“I think one of the most interesting collaborations was ’Mo Ghile Mear’ with Sting in 1985. It was such a great track. Listen to that and you can feel the love and the energy and the sheer mutual respect coming out.

“It was Paddy who brought Sting in. We went over to his wonderful mansion in Kent. I remember Paddy and The Chieftains took one flight and I had to get a different flight and get a taxi all the way from Heathrow. We went into this beautiful room with high ceilings – what he called his library. We recorded in that big room.

“He was such a lovely man, so real. He so enjoyed it. It was all a learning experience for him. This river flows into his land, but he’d put in stepping stones and split it up into loads of little tributaries. It was a beautiful garden. At dinner Sting and Derek Bell started talking about Eastern philosophy and gurus. Paddy was talking about the music, it was always about the music.”

‘The Foxhunt, The Chieftains Live in San Francisco, 1973 & 1976’ comes the ‘Bear’s Sonic Journals’ series, and is a joint release by The Owsley Stanley Foundation and Claddagh Records