The environmental ethicist Katie McShane compares our awe of the species to the word freedom. Everyone believes in it, but nobody knows what it means. “Even if you agree that it has value, it doesn’t tell you what to do if that value conflicts with my needs,” she says.

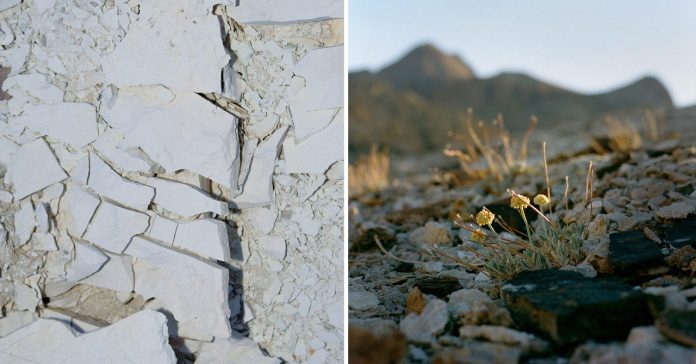

Comparing the value of things, weighing the costs and benefits of things against each other, is more and more the concern of environmentalists. Sometimes these competing things both have a claim in the natural world; sometimes one aspires to improve human life. Or the planet as a whole. If the mine at Rhyolite Ridge were digging for gold or copper, it might be easier to gauge its value. Everyone benefits from commodities, but it’s easy to say that you don’t “need” gold or that the dollar value is not in the foreground. With lithium, rejection is more difficult. Donnelly and Fraga agree that the country – the world – needs to wean itself from fossil fuels. Lithium and sunshine are abundant in the southwest of the desert, so the transition to green energy is likely to bring a new level of industrialization to the landscape. Mines and solar power plants will compete with rare buckwheat and desert tortoises. But without these mines and power plants, the desert will still suffer. Despite their harsh conditions and apparent barreness, deserts are fragile places, life there is easily endangered by higher temperatures and more frequent droughts. The conditions require that we formulate a moral equation: what is the value of the mine versus the value of the plant?

All mines have a dirty side, regardless of whether their products are “green” or not. They can destroy landscapes, pollute water supplies or emit greenhouse gases. In the past, mining companies paid little attention to this impact and did only what was necessary to comply with regulations. But lithium miners are under additional pressure to act responsibly, explains Alex Grant, a technical advisor who works with these mines. Electric vehicle buyers, for example, should ensure that 25 percent of their car’s carbon dioxide emissions come from the battery supply chain over its lifetime. As a result, to improve their climate-friendly reputation, automakers have increasingly relied on lithium suppliers to burn less coal and seek certifications that their mines do not destroy bodies of water and habitats.

It is impossible to leave out all costs. For Grant, there is no alternative to digging up lithium. The status quo of fossil-burning cars is not an option. What did opponents of lithium mining expect? A return to the horse and buggy? “We don’t need every project,” he says. “Some of them could have effects that we shouldn’t accept. But we will need a large part of it, that’s for sure. “

Each project seems to have its own cost that someone finds unacceptable, making it even more difficult to decide which projects to move forward. In the far north of Nevada, Thacker Pass, another large lithium project about to be excavated, is being held up by disputes with indigenous groups and ranchers over water rights and pollution. The same goes for places like Chile and Bolivia. Alternatives that appear more ecologically attractive, such as brine near California’s Salton Sea, have been debated for decades, but the technology and funding of these projects is uncertain. We could maybe look at the oceans; Deep-sea mining could offer lithium on a scale that would make any terrestrial mine look puny. But the environmental costs of this approach are arguably even less well understood and potentially enormous.

In this context, the fate of a humble flower seems like a very small thing when the lithium is available so quickly and with few additional complications. Mining interests, ranchers, and developers have long argued that the process of listing endangered species should take into account economic costs, such as the depreciation of a mine or the cost of maintaining a species for life when it appears that the forces of nature could choose it Existence.