Reviews & Culture

Fifty years ago this week, the Wattstax concert in Los Angeles was a fork in the road—both artistically and politically. Harold Wilson relives it in technicolour

Downloading PDF. Please wait…

Monday 15 August 2022

Issue 2818

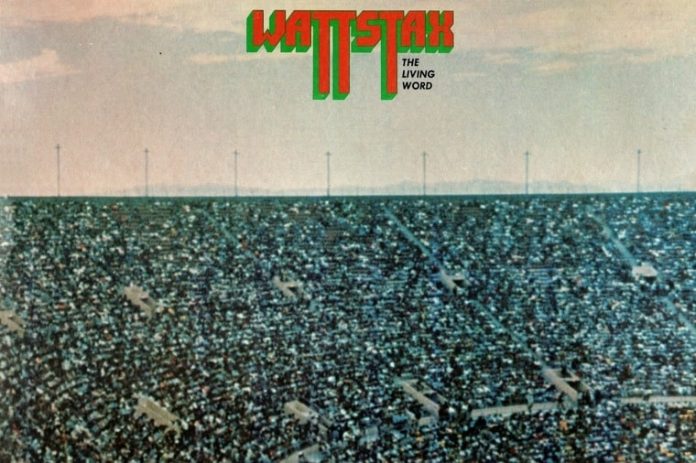

Giant crowds form the Wattstax live album cover.

“I may be poor but I am somebody. I may be on welfare but I am somebody.” Stadium compere Reverend Jesse Jackson cried out these words, beckoning each refrain to be repeated in a call and response pattern common to black churches.

“I may be unskilled, but I am somebody.” “I am black, beautiful and proud. I must be respected. I must be protected”.

“What time is it? national time!” This was the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on a hot August day 50 years ago. That crowd of concert goers took up Jackson’s rallying cry, raising fists which punctured the skies in uniform salute.

Jackson wore an African dashiki top that day, set off by an impeccably teased afro. Motown singer Kim Weston delivered a rendition of Lift Every Voice and Sing—a song billed as the black national anthem.

Wattstax was staged as a nod to the city’s urban rebellion of 1965. Watts is a district of Los Angeles. In 1965 some 20 percent of the city’s population was black and a third of them had no job.

While Stax was one of the biggest soul music labels. Riots Much as in Harlem, New York, the previous summer, the Watts riots were triggered by a seemingly mundane run-in with “the man”—white authority.

Cops had pulled a black motorist over a traffic violation but then drew their batons, clubbing a crowd that gathered to object. The response came as hundreds of people then hurled stones at passing white motorists. Cars were upended and then torched.

The action spread from there over six days. Time magazine, having grossly misread the nation’s mood, was shaking.

Its initial optimism stemmed from news of recent advances by US troops in Vietnam, plus reports of bumper crop harvests. Now, however, it shuddered at “The Negro’s unbridled rage”. It continued in that vein.

Civil rights, black power and the music at the soul of the fight

“A Negro woman tried to run a National Guard blockade and was riddled with machine gun fire,” it wrote. “An eighteen year old boy caught looting a fire-damaged furniture store was shot dead; near where he fell was a body so hideously charred that police were unable to determine the sex.

“Fifty police rushed to the Black Muslim mosque in Watts on a tip-off that arms were being laid there, arrested fifty-nine Negroes after a half-hour gun fight”. At its peak, the state deployed 14,000 National Guard soldiers.

Thirty five civilians died and 900 were injured. Property damage was said to be £40 million.

Stax was a Memphis-based soul record label, an unvarnished flip side to Detroit’s polished Motown. They propelled the Wattstax festival, lending their promotional name and supplying the artists.

Formed in 1959, Stax would achieve ascendancy over Sam Phillips’ Sun Records—the label of Elvis Presley and many early rhythm and blues artists—as the number one label in Memphis. It was home to some of the biggest names, including that man with the greatest set of pipes, Otis Redding.

Singer Rufus Thomas was a seasoned entertainer by the time Wattstax rolled into town. He arrived on stage like a cone of candy floss in matching pink cloak, jacket, shirt, extended shorts and just below knee-high funky white boots.

Thomas set about his track, The Breakdown, with joyful purpose, throwing down a trademark staccato foot shuffle. Intensity The Bar-Kays, in resplendent white, resembled a flock of seagulls. They brought an intensity heightened by a sharp-shooting brass section.

Guitar legend BB King’s gave the crowd I’ll Play the Blues For You. Its guitar bass licks and chord screams were cool enough to melt ice.

As the evening closed Luther Ingram’s confessional gospel/blues If Lovin’ You Is Wrong (I Don’t Wanna Be Right) was a beautiful lament. Isaac Hayes’ set brought the curtain down on the seven-hour festival. Sight of his stretch limousine cavalcade, his torso draped in chains and the flame orange pants he wore sent people wild.

“The revolution could not be televised”—Summer of soul review

The “Black Moses” had arrived. He performed the theme from Shaft, which had won an Oscar the previous year. But it was his song Soulsville, with its lyrical signposts to black life, that fitted best.

At Wattstax both politics and music stood at a crossroad. In his opening address Jackson proclaimed tellingly, “In Watts we have shifted from ‘burn, baby burn’ to ‘learn, baby learn’.” Street fighting the cops, and the looting and burning which had characterized the revolt of ’65, what past.

Electoral politics was now said to be the path to black freedom. Five months earlier, Jackson had met with activists and cultural nationalists in Gary, Indiana. Their purpose—which never materialized—was the formation of an electoral alternative to the twin political pillars of US capitalism, the Republicans and the Democrats.

Over time, former civil rights campaigners would run city administrations, district attorneys and heads of police departments. Stax Records also went into retreat.

With its best years of 1961-71 behind it, and unable to keep its stars, the company filed for bankruptcy. Its assets were auctioned off in 1975. Wattstax nonetheless remains a riveting all-sensory assault.